You’ll find it after the rain, half-buried

in the mud beside the garden trellis,

a smoking pale oblong orb,

hot to the touch and smelling

pungent of sandalwood and ash.

Wrap it in a towel and take it

into the kitchen, set it on

the linen tablecloth, if you dare,

but be warned: this is not a thing

to undertake lightly.

Do not be surprised if the cat

begins to yowl, if the goldfish

tries to leap out of his bowl.

The television will skip channels

and the radio might scramble

the DJ’s voice and your

mother-in-law will likely call

just to wish you a wonderful day.

This is normal in the presence of dragons.

You may need to remove the rack

to make it fit, but place it in the oven:

425 degrees for three hours

or until golden brown.

Resist the temptation to baste

it with butter, as dragons

take particular offense

to that sort of thing, and you

do not want to offend a dragon,

even one that has not yet hatched.

Feel free to go to bed,

as dragons intend to hatch

only when it is convenient

for them to do so,

and it is most convenient

for them to do so about

an hour after you’ve

finally fallen asleep

on the night before your

busiest day at the office.

You will jolt awake at

the sound of a shriek and

a crash from the kitchen.

The cat will hide behind

the potted plants and

the goldfish will likely

bury himself in the gravel

at the bottom of his bowl,

and you may find yourself

wishing you could join them.

This is normal in the presence of dragons.

Put on a terrycloth robe

and sneak downstairs

to find it gnawing on

the kitchen table’s leg,

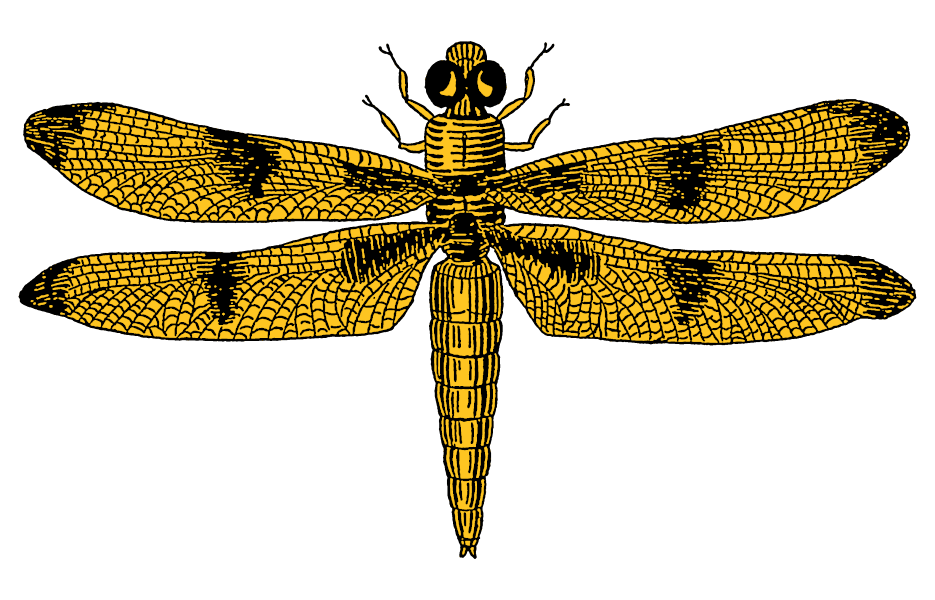

a gangly red scaled thing,

wobbly and uncertain on its

newborn sharp-clawed feet.

The stove will be a smoking twist

of metal, and I’m very sorry for that:

I should have warned you that

hatching a dragon is not much

like hatching a chicken or a duck,

and there may be a reasonable

amount of collateral damage involved.

Quiet though you are trying to be,

dragons have remarkable hearing,

and it will look up at you with

large gold eyes and open a healthy

mouth full of bright jagged teeth

and croon happily at you before

scuttling across the floor

to sit at your feet. Stare down at it,

sick with the sudden sinking feeling

that you are not ready to be a father.

This, too, is normal in the presence of dragons.

This poem was originally published under the pen name Gabriel Gadfly.